Meet Maximón, The Mayan Saint Watching Over Bar Ilegal

The Guatemalan Patron Saint of Vices has a long history with the Ilegal Family.

By E.R. Pulgar

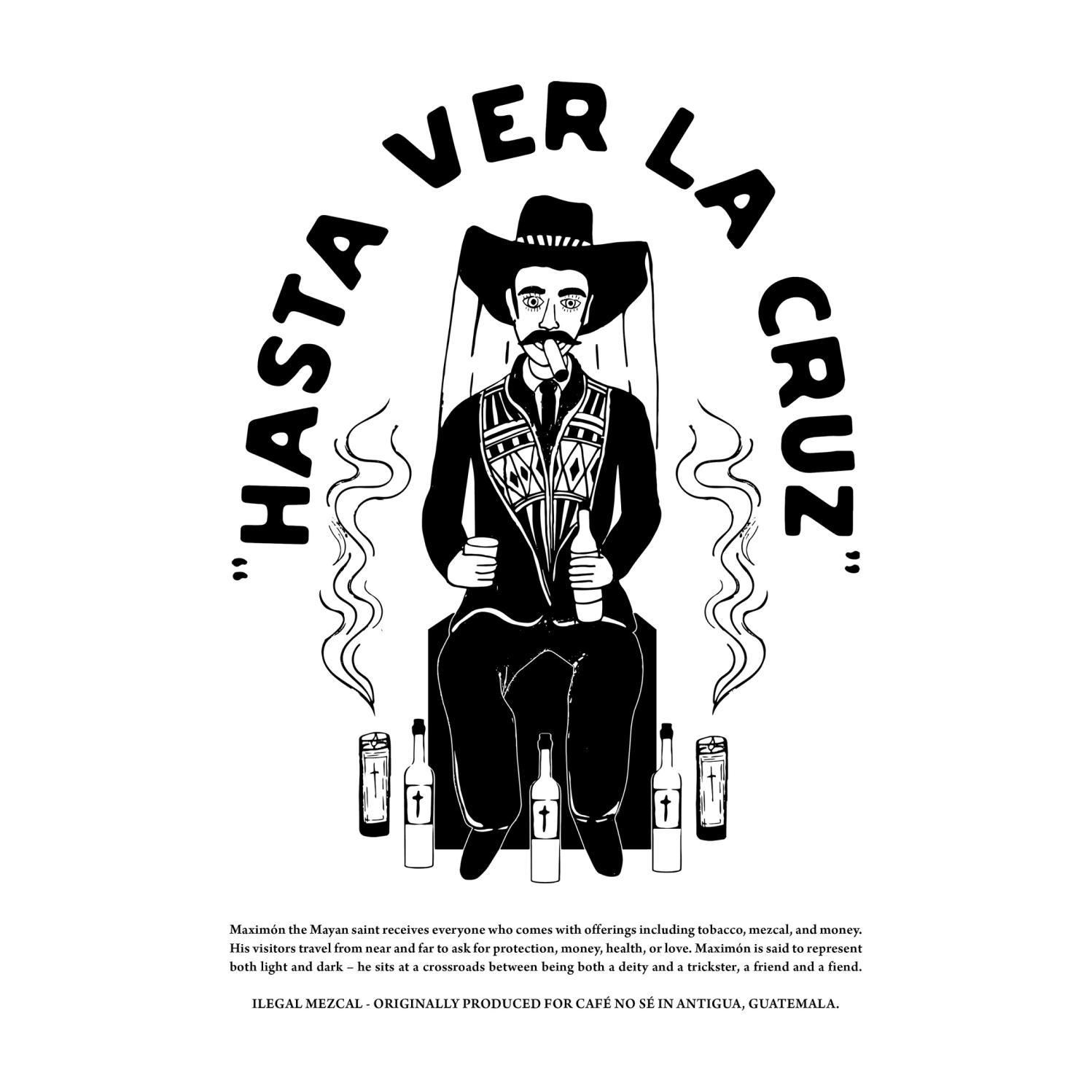

Enter any of our spaces, be it Bar Ilegal in Oaxaca or our flagship space Café No Sé in Antigua, and you’ll find a familiar friend lurking underneath the dim candlelight. If you look carefully, you’ll find yourself in front of a nook replete with flowers, cigars, sweets, money and shots of mezcal left in reverence. These offerings are for a man of many names, a small Mayan man in a hat, a colorful scarf, and sunglasses who could drink you under the table.

He’s a regular, and he goes by many names: San Simón in Guatemala, Don Monchito by disciples, El Gran Abuelo by family. More widely, and to the Ilegal family, he’s known as Maximón. His story is a winding one. Mainly revered these days as a folk saint of vices, he’s gone through several incarnations, taken many guises, and left quite a reputation.

We describe him on our website as sitting “at a crossroads between deity and trickster, friend and fiend.” Indeed, he’s known by those who revere him as both mischievous-maker and protector. Morally sitting somewhere between the Greek god of communication Hermes and the Zulu troublemaker spirit Tokoloshe, Maximón is the embodiment of the two-sided coin of good and evil that is humanity. He is a womanizer who is also the protector of couples. He is a grandfather and a partner-in-crime. Perhaps the most important aspect we associate with him is Guatemalan Indigenous resistance.

His syncretized mythos spans Mayan history, the horrors of Spanish colonialism, and the life of a Mayan elder named Ri Laj Mam. According to one legend, he encouraged an uprising against the Spanish colonizers who were attempting to take Guatemala in the late 1500’s and was executed for revolting. He is said to have reincarnated as a judge named Don Ximon, a steadfast advocate for landback policies for Indigenous Guatemalans. Another myth speaks of a picaresque Don Juan figure — hired by traveling fishermen to protect their wives while they were at sea, he went on to sleep with all of them before skipping town. Others whisper of a trickster spirit who was subdued by the shamans of Santiago Atitlán and went from being a terrorizing force to a protector of evil. In the temple attributed to him in the Guatemalan town of Santiago Atitlán, special attendants accompany his effigy by drinking and smoking the night away as they stand guard alongside it.

That Maximón’s following continues to be so fervent in Guatemala speaks to the tight-knit nature and love present in the contemporary Indigenous Maya community. During the early 1980s, the Guatemalan military undertook a notorious “counterinsurgency operation” targeting Maya peoples and alleged communists. Now known as the “Guatemalan Genocide” — to some, “The Maya Genocide” or “The Silent Holocaust” — the mass-killing left between 30,000 and 166,000 Maya dead or disappeared by the government amid the backdrop of a civil war and targeted anti-Indigenous sentiment. The survival of Maximón’s mythology — that he is a protector of lovers and freedom fighters alike — and his reverence is proof positive that they failed.

His feast day is October 28th. On that day be sure to pour one out and raise a glass to an icon of Indigenous communities thriving in Guatemala, our protector of the bar, our jokester elder. Maximón’s totem is present at Café No Sé and Bar Ilegal because he is present where a good time is happening, where music rings from the windows and out the speakers, where people are meeting and drinking and talking of resistance and falling in love.

Originally published in Ilegal Mezcal Newspaper, Vol. 5.